As colleges across the country adopt corequisite remedial models—which enroll students directly in college-level courses with concurrent academic support—higher education policymakers, educators, and advocates are eager to see more research on its effectiveness. In a new CCRC working paper based on data from the 13 community colleges in Tennessee, we provide the first causal evidence of the effects of corequisite reform on student outcomes across an entire college system.

Our study confirmed earlier research showing that corequisite remediation results in much higher gateway pass rates than traditional prerequisite remediation. For students on the margin of the college readiness threshold, those placed into corequisite remediation were 15 percentage points more likely to pass gateway math and 13 percentage points more likely to pass gateway English within one year of enrollment than similar students placed into prerequisite remediation. That is nearly a 50% improvement for math and more than a 20% improvement for English. Combined with strong experimental evidence for corequisite remediation from three community colleges in the CUNY system, our results provide further evidence that corequisite remediation is much more effective than the traditional prerequisite approach in helping students get through their first college-level math and English courses.

What’s New in Our Study?

But what accounts for the positive effects of the corequisite model? Given what we know about how traditional prerequisite remediation affects students, it is perhaps not surprising that corequisite remediation is more effective. But it is not clear that the extra support is what makes the difference. In fact, students placed into corequisite remediation had gateway completion rates in math and English that were similar to students who avoided remediation by scoring just a few points above the college-ready threshold on a placement test. This suggests that students on the margin of the college-ready threshold would have done just as well if placed directly into a college-level course. Thus, the main advantage of corequisite remediation, at least for students near the college-ready threshold, is that students can take college-level classes right away and avoid spending one or more semesters in prerequisite courses, which hold students back.

In addition, we found that improvements in pass rates in gateway math in Tennessee were mostly driven by math pathways reforms that guided students into math courses aligned with their programs of study. Traditionally, new students entering community colleges in Tennessee were required to take courses on the algebra track, which is standard practice nationwide. Since the math pathways reform, more than half of entering students in Tennessee instead take statistics, the more appropriate math course for social science and other non-STEM majors. Fewer than 20% of new students remain on the algebra track, while the rest take math for liberal arts or other program-specific math. We found that students placed into corequisite statistics had significantly higher gateway completion rates than those placed into prerequisite algebra, and that students placed into corequisite algebra did not benefit significantly from their learning support courses. This shows that expanding options for math that address students’ needs in their majors and career tracks has been essential to remedial math reforms. It also shows that future research needs to look into promising curricular designs and instructional practices to improve outcomes in algebra and other math courses for STEM fields.

Informing College Practice and Future Research

This new understanding of the mechanisms behind the improvements in success rates for corequisite students has significant implications for colleges, yet there are still many unanswered questions about how to design effective remedial programs.

1. What approaches are effective for students who arrive at college very poorly prepared to succeed?

Community colleges serve highly diverse student populations; it is unlikely that one solution can address the academic needs of everyone. For corequisite students who missed the college-level cutoff by only a few points, our study shows that they can succeed in gateway courses without any remediation at the same rate as students just above the cutoff. It may be beneficial to make corequisite support optional for these students, as they could have better ways to use the time and money consumed by corequisite courses. Colleges and state systems should also consider using multiple measures, including students’ academic records from high school, to identify those truly in need of remedial support. Big changes like these require a shift in mindset around the purpose of college remediation, from diverting students deemed “underprepared” from taking college-level courses until they appear ready, to maximizing the chances that students will complete their first college-level math and English courses without delay.

At the same time, more than one study has shown that students with lower levels of academic preparation can benefit from an intensive focus on building basic academic skills, either in prerequisite remedial sequences or in programs providing a prescribed instructional approach taken before college matriculation. It is important to understand how lower-scoring students, who presumably are more academically vulnerable, are best served.

2. What specific corequisite practices are most effective in different subjects and with different student groups?

One important caveat to research in this area, including my own study, is that when researchers use the umbrella term “corequisite remediation,” they are in fact referring to models with many variations. In Tennessee, it means an up-to-three-credit learning support course paired with gateway math or English, delivered either face-to-face or in computer-aided lab sessions; in CUNY, it means a weekly credit-bearing statistics workshop led by advanced undergraduate or graduate students; in Texas, corequisite models include instructor-facilitated lab sessions, extended instructional time, and paired courses, among other alternatives. Even though current evidence suggests that no corequisite model is worse than the traditional prerequisite approach, institutions and states designing their own reforms could benefit from more nuanced examination of how variations in corequisite implementation affect its effectiveness.

3. How can colleges eliminate equity gaps in outcomes that we see even in corequisite models?

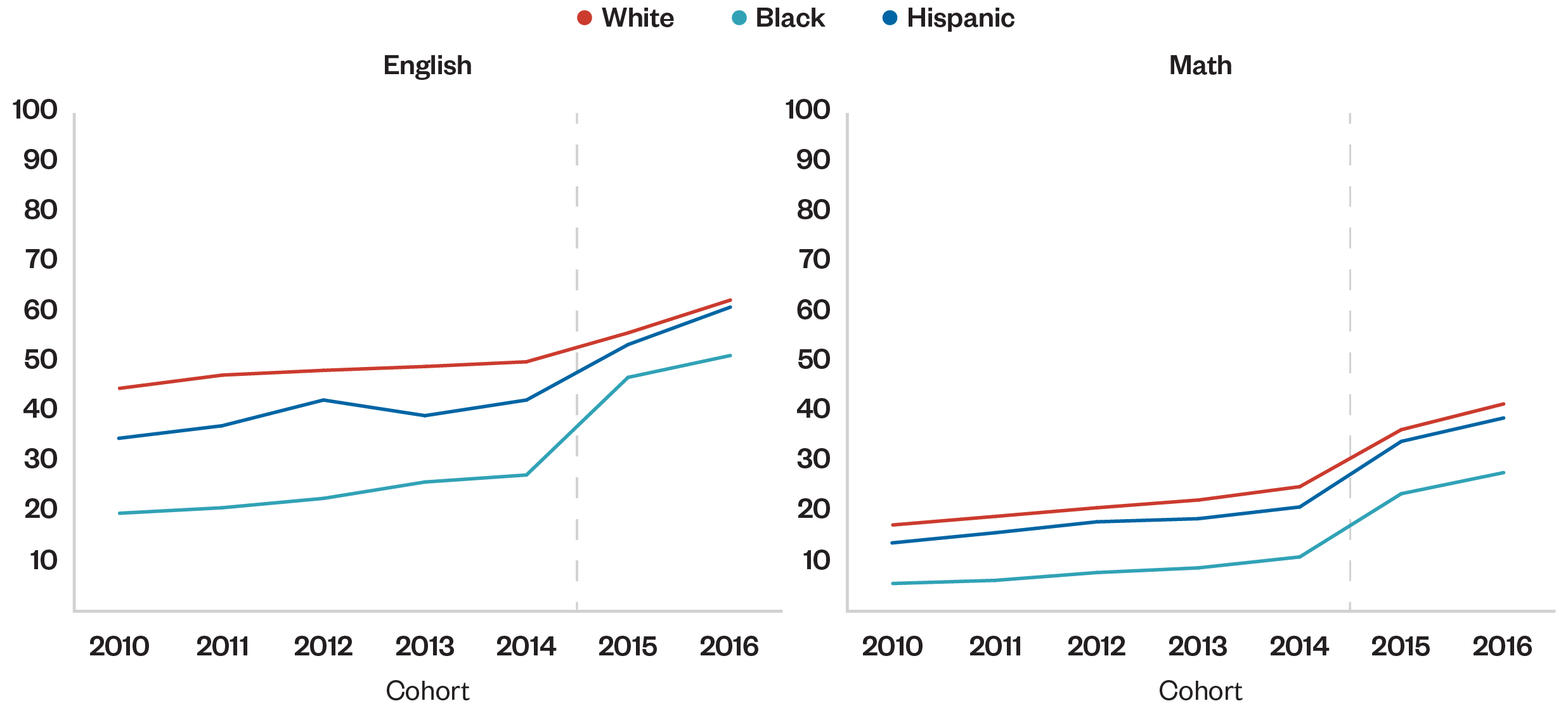

Since Black and Hispanic students are disproportionally likely to be referred to remedial courses, traditional remediation unwittingly serves to exacerbate inequality in postsecondary education. Corequisite remediation has been shown to be more effective for all demographic groups, compared with traditional prerequisite models. But does it work to close racial gaps in college outcomes? Our internal analyses using the Tennessee data show that first-year gateway completion rates improved across the board over time, and some differences across subgroups did narrow. However, we also found that substantial gaps remained between White and Black students. Moreover, rather than asking merely whether a remedial reform works for all students, a greater focus on equity may lead to a broader question: What more should be done for Black and Hispanic students and those who have been historically marginalized in higher education?

Source: Author’s calculations based on student transcripts from 13 community colleges affiliated with the Tennessee Board of Regents.

In the past decade, state systems and colleges have been rethinking and reinventing developmental education. Corequisite remediation is one promising example of new models that may lead to improvements in student outcomes. However, the progress should not end here. Colleges, state systems, and researchers should continue their work to identify and address the barriers that are preventing access to and success in college.