By Davis Jenkins and Clive Belfield

For the past five years, CCRC has been studying how community colleges are implementing guided pathways reforms, which are designed to strengthen support for students to choose and complete a program that leads to a good job and further education. With guided pathways, colleges are transforming how students experience the institution through major changes to academic programs, advising, instruction, business processes, and information systems.

Since the COVID-19 crisis began, CCRC has conducted formal interviews; run online workshops; and otherwise talked with administrators, faculty, and staff at colleges in numerous states across the country about their work on guided pathways whether their plans are changing as a result of COVID. Our sense from these interactions is that not only are colleges moving ahead with these reforms, but interest is also growing among colleges that are not yet part of the pathways movement.

We just published a new analysis showing that implementing guided pathways requires additional resources, which while modest (about 3% of annual operating budgets for the “average” community college) are not insignificant. So, why are community colleges continuing to invest in guided pathways reforms—especially now, given the increased uncertainty about enrollments and cuts in state funding resulting from COVID?

Some possible answers to this question can be found in another CCRC publication we just released: a practitioner guide to funding guided pathways. Leaders of colleges that have institutionalized guided pathways practices despite the added costs say the reforms have led to improved outcomes for students and benefited the colleges as businesses. They also say that the guided pathways reforms made it much easier to respond when COVID-19 hit.

How much do guided pathways reforms cost?

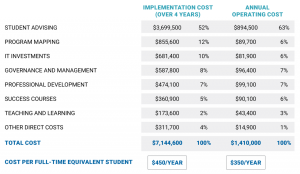

The table below shows the estimated costs of guided pathways at an “average community college” (one with a full-time-equivalent enrollment of 4,000 and an annual operating budget of $60 million). We calculated these costs using data from over 100 interviews with college personnel and documents from 12 colleges across the country, which as a group are similar in makeup and funding to community colleges nationally.

Estimated Costs of Guided Pathways at an “Average” Community College

Source: The Economics of Guided Pathways: Cost, Funding, and Value (Belfield, 2020).

For this “average” college, we estimate that implementing guided pathways reforms costs $7.15 million over four years, which is typically the time it takes for colleges to implement core guided pathways practices at scale. This works out to about $450 per full-time equivalent student per year of added costs, or an additional 3% of annual operating costs.

The largest start-up cost is hiring additional advisors to allow individualized case management of students by field or meta-major. Other substantial start-up costs include providing faculty and staff release time to engage in program mapping, as well as purchasing or upgrading information technology systems to support websites, online catalogs, individualized advising, academic planning, progress monitoring, and class scheduling. The estimated cost of sustaining guided pathways reforms after the initial implementation phase is somewhat lower: about $350 per full-time equivalent student per year. Here again, the largest ongoing cost is maintaining enough advisors to allow case management of students by field.

Why are colleges continuing to invest in guided pathways reforms despite added costs?

CCRC’s new practitioner guide to funding guided pathways reforms is based on research at six institutions that have implemented major changes in programs, practices, and systems using the pathways model over the past six years. These reforms include redesigning the new student experience so that all students are helped to explore career and college options and interests and assigning an advisor to every student based on their field of interest. Advisors help students develop a full-program plan during the first term based on program maps created by faculty, monitor their progress, and ensure they complete their programs on schedule.

All six institutions shared evidence of improved student outcomes that they attribute to their pathways reforms. All six colleges saw increases in early credit momentum for first-year students. Four colleges reported increased Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) retention and graduation rates and reductions in non-degree-applicable credits. And all four institutions in states with performance funding achieved substantial gains from those policies.

Moreover, in interviews conducted over the summer, leaders at every college indicated that they were better positioned to respond to the COVID-19 crisis because of changes they made as part of their pathways reforms. Adelina Silva, the vice chancellor for student success at the Alamo Colleges in Texas, said, “The fact that every student had a plan and now we had to pivot to move online, that didn’t change their plan or their commitment to their plan.” She added that because every student had an assigned advisor in their field of study who was monitoring their progress, it was relatively easy for the colleges to reach out to students after the crisis hit. Silva and leaders from other colleges also said that because students already had plans laying out what courses they needed to take next, registering students for summer and fall courses was no more difficult than usual despite the challenges posed by COVID.

While all six institutions raised at least some grant funds (including awards from Title III and Title V) to support start-up activities around pathways, the colleges relied as much on reorganization, reassignment, and reallocation of staff and resources as on raising new income to cover most of the ongoing costs of the reforms. Colleges were able to shift considerable resources from disconnected reforms to strategic, whole-college redesign. Dr. Alex Johnson, the president of Cuyahoga Community College (Tri-C) in Ohio, said that when he came to the college in 2014, there were roughly 90, mostly small-scale student success initiatives, which were absorbing a lot of staff time and resources. The college stopped most of these efforts, reallocated staff and other resources, and invested in a case-management approach to advising that was organized around meta-majors and program maps. In this way, according to Dr. Johnson, Tri-C was able to reallocate $6.4 million in FY21 for pathways and related student success efforts (about 2.3% of the college’s annual operating budget of around $283 million).

What does this mean for community college funding strategies in a post-COVID world?

In sustaining support for guided pathways reforms, the leaders of these institutions are, in effect, adopting a new community college business model. In the conventional model, colleges generate enrollment and revenue by offering a diversified set of courses and programs at a low cost. In the new business model exemplified by the six case study colleges in our guide, colleges attract and retain students (and thereby increase tuition and state subsidies, including performance funding) by offering affordable programs and student supports that have clear value for employment and further education.

These college leaders and others across the nation believe that, in the face of an increasingly challenging and competitive higher education environment, investing in whole-college reforms is increasingly necessary for community colleges to continue to achieve their educational missions and survive as businesses.

Davis Jenkins is senior research scholar at CCRC. Clive Belfield is a professor of economics at Queens College CUNY and a CCRC research fellow.