Assume that full-time students are on campus about 15 hours a week, or 180 hours in a typical 12-week semester. During that semester, they are likely to spend about four hours total interacting with student support staff, 32 hours walking around, and 144 hours in classrooms, interacting with and learning from faculty. Because of this more intense interaction, faculty are the people who convey to students that they belong in college, that they have the capacity to learn, and that someone cares about their progress (or not).

Despite the huge role of faculty in students’ life on campus, many past interventions designed to keep students in school and improve completion rates have focused on other types of interventions and seen small or no improvements. For example:

- A meta-analysis of freshman seminar courses found that they were likely to increase year-to-year persistence by about 5 percentage points.

- An experimental study of learning communities found no net impact on student persistence.

- A study that looked at individual coaching of students found a 5-percentage-point increase in year-to-year persistence.

One reason for the small gains may be an obvious one. While students are affected by structural and administrative changes, on most days, they are in the classroom. And the people who most influence their college experience are faculty, a view supported by research on the role of faculty in student persistence.

Faculty at Oakton Community College in Illinois, inspired by work undertaken at Odessa College in Texas and their Achieving the Dream coach, Brad C. Phillips, have decided to take on encouraging student persistence directly by starting the Faculty Persistence Project (FPP). With leadership from Hollace Graff, department chair of Humanities and Philosophy, and Eva de la Riva, chair of Behavioral and Social Sciences and professor of psychology, they have developed a faculty/student engagement protocol in which each student becomes known as an individual person and learner.

Faculty Activities in FPP Course Sections

| First Three Weeks of Class | Rest of the Semester |

|---|---|

|

|

Note. This table is adapted from an Oakton Community College presentation at the 2018 Achieving the Dream conference.

In addition to their main role—teaching their subject matter—participating faculty have agreed to follow the steps above in one course per semester. The results have been impressive. College President Joianne Smith reports that students are asking for more of these kinds of interactions. And almost as importantly, large numbers of faculty report that using this approach has been deeply personally and professionally satisfying.

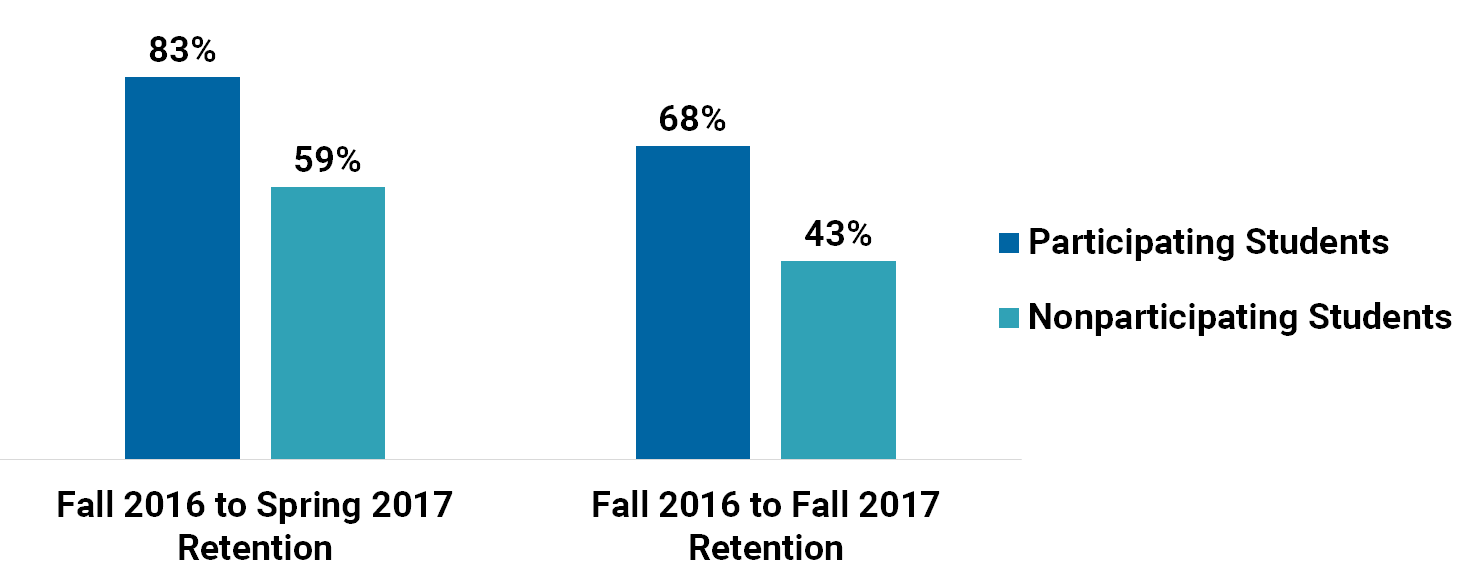

In the fall of 2016, the first year of the project, 132 faculty participated in the project, with many more volunteering than expected. A total of 1,200 students were in FPP course sections, which accounted for about 25 percent of all course sections offered. Students ended up in these sections more or less randomly, and most were in only one FPP course section. Overall, participants in FPP courses were much more likely to persist, with differences between participating and nonparticipating students of 24–25 percentage points—much higher than the impact found from other initiatives.

It is important to note that the approach has challenges. As Dr. Graff points out, the conversations with students held at the start of each semester surface many life challenges, and that can be a lot for faculty members to take on. Further, the FPP approach requires a significant time commitment for busy people who already have a lot on their plate, especially adjunct faculty members. In response, college and faculty leaders are in the process of thinking through how to address some of these issues, with attention given to union requirements and overall sustainability.

While the FPP model appears to be very promising, more work needs to be done to fully integrate this approach into the daily life of colleges. In addition, research is needed to further validate the approach and examine the ways that student outcomes are affected over time—and the impact on different student populations.

For more information on the Faculty Persistence Project at Oakton College, contact Joianne Smith at joismith@oakton.edu.