When I left CCRC last year after nearly two decades, I was eager to use research, rather than produce it. But it wasn’t long before I found there was a gap in our reform ecosystem. There are strong national and state-level resources for helping colleges identify evidence-based reforms that their students could benefit from. Institutes, conferences, and state-level meetings are fantastic venues for sharing research and high-level approaches, and for helping college personnel understand the different pieces of the reform toolbox.

But what happens when participants get back to campus? Often, they struggle to knit together an institutional model. They lack the time, or the resources, or a college culture that enables the hard conversations undergirding the reform development process. As a field, we are still trying to figure out the best approach to deep-dive, college-specific technical assistance focused on bridging high-level reform ideas and day-to-day implementation.

Now, as a consultant working with foundations, colleges, and nonprofits to help turn the principles of guided pathways, advising redesign, and broad institutional transformation into actual strategies and plans that can play out on individual college campuses, I have been thinking more about what it means to turn research into institutional change. I’ve also begun to think about implications for the broader reform landscape: Are we effectively supporting colleges in their work? What else do practitioners need to move from evidence to action?

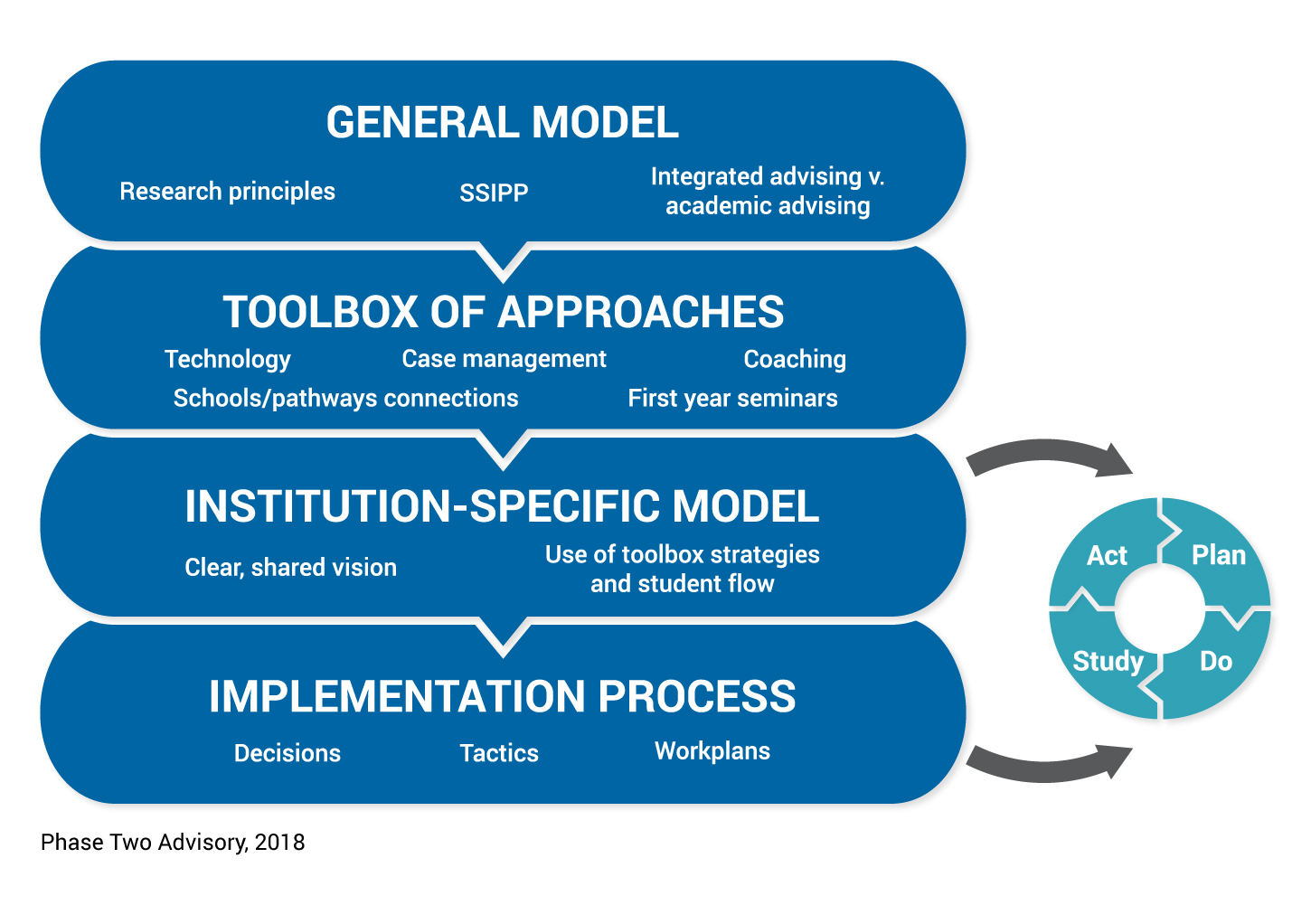

At my firm, Phase Two Advisory, we have developed a flowchart illustrating the way that research evidence moves from theories and principles to tactical change. Although the illustration shown here refers to advising and student services redesign, a similar process plays out for other domains as well. Reforms start as a generalized model rooted in research evidence (“guided pathways,” “SSIPP advising,” etc.). This generalized reform model suggests a toolbox of strategies.

Theory-to-Action Approach

Note, however, that a “toolbox” implies that there isn’t one singular approach, nor is there a clear recipe generated by a general reform model. This is one of the biggest lessons of Phase Two’s first year: There is no one “right” way.

The strategies that make sense on one campus may not work on another. For example, student success courses are a promising, evidence-backed practice that can help students identify programs of study and develop long-term program plans. Some Phase Two clients want to leverage them, and build them into their reform redesign. Others, however, cannot get traction for student success courses due to faculty resistance, union contracts, or limits to program credits. Those institutions need to find other strategies, such as orientations or workshops, to achieve the same goal.

Which leads us to the next phase of the approach—developing an institution-specific model. What will a reform look like on any given campus? How will the different pieces of the toolbox fit together in the creation of an overall model? I have found that this is where colleges get stuck. They know they want to “do” guided pathways or advising redesign, but aren’t quite sure what that will look like in practice. Instead, they jump down to the final stage of the process, planning for implementation. However, in absence of a clear vision of what they are implementing, they spin their wheels.

This is not especially surprising. Research in change management, including that undertaken by noted authors R. Heifetz and A. Kezar, has pointed out that when faced with a big, thorny challenge with an uncertain solution, individuals tend to gravitate toward questions with clear answers. When I was at CCRC, we saw this process play out among many of the colleges we worked with. And in my work over the past year I have similarly seen that within the community college reform movement, even the most thoughtful of us often jump toward implementation questions before we finish mapping out the vision, including figuring out how the model will play out in everyday experiences of different stakeholders.

At Phase Two, we spend a lot of time working with our college partners to focus on developing institutional models and getting them right (or close to right) before moving into the implementation phase. Doing so, we have found that planning needs to be detailed and strategic. It isn’t enough to say, for example, that you are going to implement new placement processes, or even to articulate what those processes will be. Colleges need to think about what the changes will mean in practical terms for an array of stakeholders. What types of messages will students need to receive, and from whom? How will the workflow in admissions change, and what expectations will enrollment officers be held to? If the composition of gateway courses will change, what types of pedagogical approaches will faculty need to use, and how will the college support them in doing so? In other words, what will the reform look and feel like on a day-to-day basis for college personnel and students? Answering these questions helps clarify the outlines of the reform, while also guiding project leads toward the most critical implementation tasks.

The flow chart embeds a continuous improvement cycle adapted from the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. This is critical. It sends a clear message that we won’t always get it right the first time, and that’s okay. Sometimes colleges are so worried about getting their reforms perfectly designed and launched that they end up not doing anything at all. It’s time to start taking the notion of reform as a process more seriously—reform includes reflection, iteration, and improvement. Make the experience for students better than it was before. Then, if the results still aren’t what were hoped for, identify ways to make it better once again. And so on.

The energy around reform among community college personnel is exciting and inspiring. Meeting with like-minded colleagues is a critical piece of shifting college-based practices. But it’s what happens on campus that will really lead to changes students can feel. Designing and shepherding change, campus by campus, structure by structure, is the slow, steady, most challenging and, I’d argue, most important, piece of the reform puzzle.