Experts on the future of work say that much of the workforce is at risk of becoming obsolete because of the spread of computers, robots, and other automated technologies. While funneling more 18-year-olds into higher education might have been a solution in the past, a shift in the population of students may warrant a new approach to educating members of the future workforce. Because more students are older and already working, it is critical that their studies lead directly to better jobs.

Michelle Weise, the chief innovation officer at the Strada Institute for the Future of Work, said those facts shape how she and others think about how the higher education system can evolve to fit the needs of the future workforce.

“We are going to have to start to prepare learners for work that just doesn’t exist yet,” said Weise, who spoke in May at Teachers College as part of a series organized by CCRC.

Courtesy of Michelle Weise

Courtesy of Michelle Weise

Strada Education Network is a national nonprofit dedicated to improving lives by catalyzing more direct and promising pathways between education and employment. Weise’s charge at Strada is to understand labor market trends to inform strategic investments to build a viable workforce for the future.

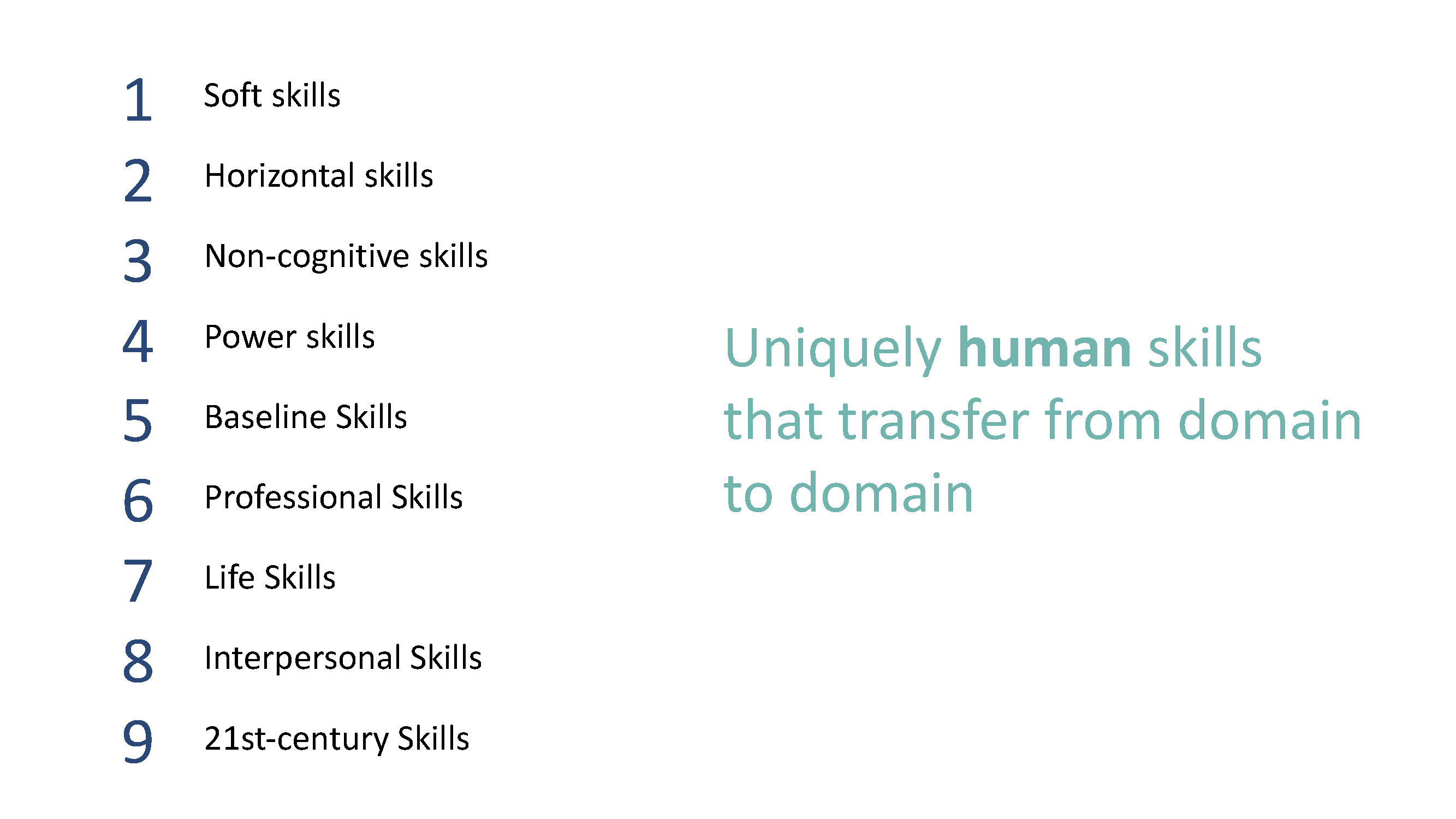

Some jobs will inevitably be automated, she said. But there will continue to be a demand for workers who cultivate uniquely human skills that can transfer across jobs and evolve with work, like communication, leadership, and problem-solving. The demand for those skills is already becoming evident in job postings, she said.

Despite the devaluation of liberal arts degrees in the current conversation about college and careers, it is often history, English, and other humanities majors who develop these critical skills in college. Data show that liberal arts graduates are well positioned to enter promising jobs like marketing, human resources, management, and financial analysis, Weise said. But though their degrees may pay off in the long run, liberal arts majors are more likely to take longer to land in a high-skill, high-wage job and remain underemployed longer than their STEM major peers.

This is in part a translation problem, Weise said. Employers need to get better at conveying what skills they need in an employee. They also need to recognize that skills such as management, communication, writing, and critical thinking take time to develop and that learning opportunities should be embedded in the workplace.

The work to bridge this gap doesn’t fall solely on employers, however. Learning providers also need to marry the development of human skills and technical skills that are in demand in different industries.

“We are going to have to think about how we connect to those learning experiences that might give us both broad-based and technical skills,” Weise said.

Another concern is how to help workers maintain and update their skills when they leave and reenter the workforce (for instance, taking time away from a career to care for family members). A Strada report on short training programs designed to reskill older workers found that they had significant success in placing students into jobs but served relatively small numbers of students. Figuring out how to scale such programs through workforce development boards, community colleges, private colleges, and other education providers is both the challenge and the opportunity ahead.

“How are we going to actually make our systems feel less brittle and less rigid?” Weise said. “Instead of trying to think about education as this linear process—where it’s education, work, retirement—we’re going to have to think about this as perhaps more of a series of on- and off-ramps that we have to build into the system.”