By Lauren Schudde and Wonsun Ryu

Dual enrollment—also known as concurrent enrollment or dual credit—offers high school students the opportunity to earn college credits. To facilitate high school students earning college credit, postsecondary and K-12 educators must collaborate to make decisions about dual enrollment course offerings, resource allocation, and instructional staffing. The decisions that they make can shape students’ success in dual enrollment and beyond. These decisions are complex—especially for colleges managing dozens of partnerships with high schools. Understanding variation in dual enrollment outcomes across partnership-level characteristics could help high schools and colleges improve program structures to promote dual enrollment and postsecondary success.

In a new CCRC working paper, we examined variation in dual enrollment (DE) partnerships across Texas and estimated how characteristics of these partnerships predict student success. Using administrative data from the Texas Education Research Center, we constructed a partnership-level dataset of high school–college pairs and tracked aggregate student outcomes across three high school cohorts. Based on prior literature illustrating variation across DE partnerships, we anticipated that some partnerships may have stronger outcomes than others and that partnership characteristics could predict partnership-level outcomes. Thus, we characterized DE partnerships in terms of which students gain access to them (demographic makeup and test scores), contexts of partnering institutions (including variation in resources, geographic location, presence of an Early College High School [ECHS], and student composition), and course availability and structures (e.g., career and technical education [CTE] or transfer-oriented, course location, modality, instructor type, and subject area).

Among numerous differences we captured in how partnerships implement DE programs, we found that—controlling for a rich set of institution-level factors—two key factors overshadow all others in explaining student postsecondary outcomes after high school: the geographic setting of the high school (particularly rural vs. urban locales) and the availability of ECHS opportunities.

Here are the key findings from our paper:

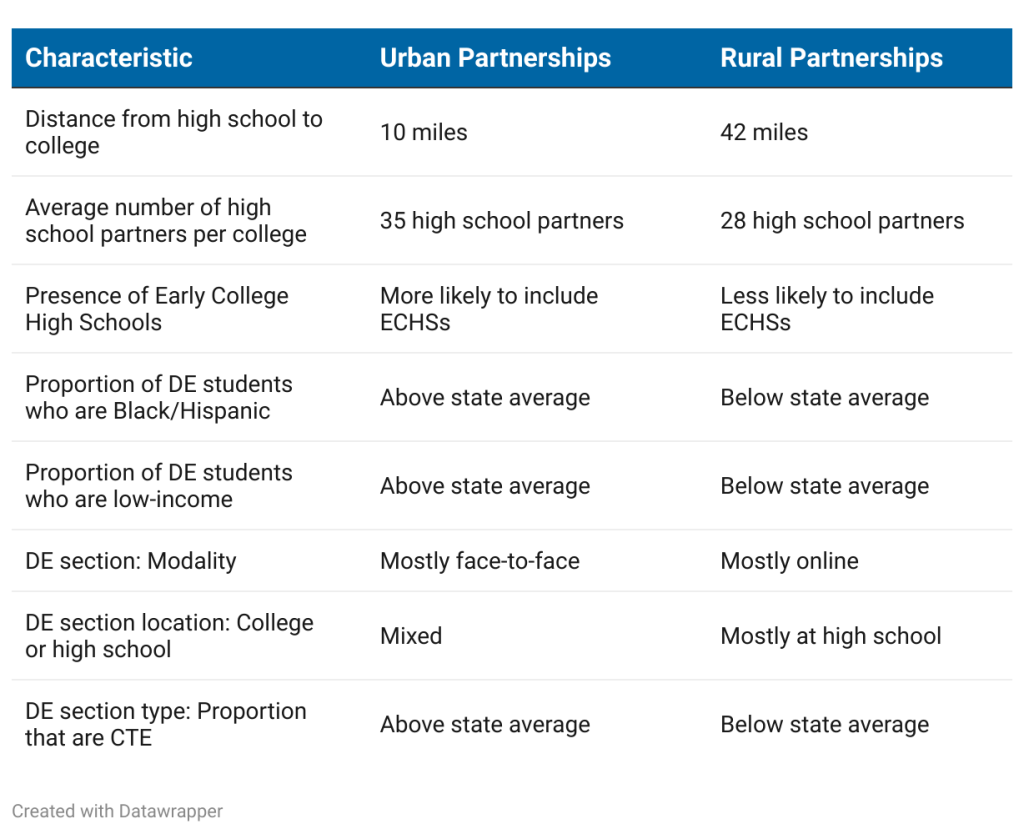

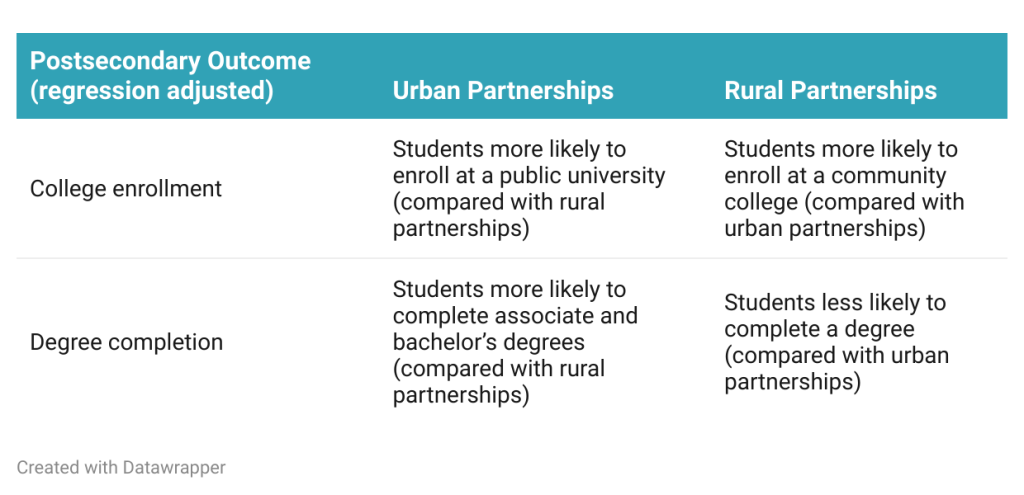

- There are dramatic differences in partnership characteristics and outcomes across geographic locale, particularly for rural and urban partnerships. We outline some of these differences below:

- Partnering with Early College High Schools, which tend to offer structured DE course sequences, strongly predicts a DE partnership’s aggregate student success, even after controlling for partnership and institutional characteristics. Holding all other variables constant, partnerships with an ECHS—compared with a traditional high school—are associated with a 26-percentage-point increase in students’ associate degree attainment rate and 20-percentage-point increase in students’ public university enrollment rate.

- There were very small relationships between many other partnership characteristics (e.g., course type and instructor affiliation) and aggregate student outcomes. We take this to mean that simple malleable shifts in the number or type of DE course offerings are unlikely to move the needle for DE partnership outcomes, though there may be unmeasured partnership practices—not captured in administrative data—that do. Rather, our results suggest that addressing disparities related to geographic locale and access to ECHS opportunities may be more consequential.

Overall, our findings show that rural and urban DE partnerships differ in several ways and are associated with different aggregate student outcomes. States and local stakeholders supporting DE program improvement likely need to differentiate supports for rural versus urban partnerships based on these differences.

Leveraging resources to make targeted investments based on DE partnership context may be useful in strengthening DE partnership outcomes. For example, our results illustrate that urban community colleges have, on average, fewer resources per student than other partnerships, yet they serve disproportionately more racially minoritized students and students from low-income families. To improve racial and socioeconomic gaps in DE access and college attainment, pursuing grants and community-based partnerships to offer additional student supports—such as tutoring and academic advising—may be especially useful in urban settings. Rural partnerships rely heavily on online DE—71% of their DE sections are online—due to their distance from partner colleges. They need to invest in supports for effectively facilitating online coursework, which is known for lower student engagement, such as assigning support staff to serve as course facilitators so students have an in-person contact during their course period. Finding additional options to connect the rural DE students to the college campus, including occasional campus visits, could also improve ties between the students and the community college.

Finally, given the higher aggregate outcomes for ECHS partnerships, it’s essential that future research further examine how to expand what works well about the Early College High School model for students taking dual credit courses outside of that model. We anticipate that some of those components will align with the DEEP model, including aligning DE offerings to college degrees, ensuring strong advising and pathway planning toward a credential and career, and providing academic support opportunities for all DE students. Continued research into DE practices may also further explain variation in aggregate outcomes across the board in ways that can inform next steps for DE program improvement.