Dual enrollment (DE), in which high school students take college courses, has great potential to help make the high-school-to-college transition more effective and equitable—and to do so on a large scale. DE is distinguished from other approaches to earning college credit in high school, such as Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate, because it requires a partnership between a high school and a postsecondary institution that awards the college credit. DE encompasses a wide range of program designs, from immersive early college high schools (ECHSs) to much more common à la carte models in which students take one or more college courses taught either by a faculty member or by a qualified high school teacher.

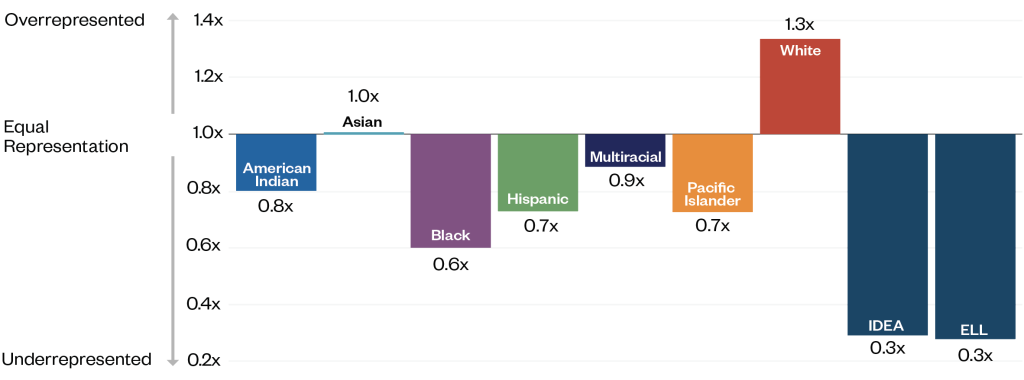

Representation in Dual Enrollment

What the Research Tells Us

Dual enrollment is widespread, and high schools offer it most often in partnership with community colleges. Dual enrollment students are a growing portion of community college enrollment.

- Nationally, 82% of high schools offer DE courses.[1] About one third of high school students have taken at least one DE course by graduation.[2]

- Among 2019 high school graduates who took DE, the top subjects were career/technical courses (44%), English (37%), social sciences (31%), and math (29%).[3]

- More than 2.8 million students enrolled in DE courses in 2023-24, two million (71%) of them at community colleges.[4] From 2013 to 2023, the number of students taking DE nearly doubled, and it continues to grow.[5]

- High school students account for more than one in five community college enrollments.[6][7] Many former DE students transfer a substantial number of credits.[8][9]

There are several different models of dual enrollment.

- DE is an umbrella term that encompasses various models of early college programming. Some examples include concurrent enrollment (a student takes a course at their high school while receiving college credit), dual credit (a student earns both high school and college credit), and ECHSs, an intensive model in which students may earn associate degrees by high school graduation.[10]

- DE course features may affect student course completion and college-going rates.Taking courses on a college campus rather than at the high school is associated with a lower probability of passing but a higher probability of enrolling at a community college after high school. Taking DE courses online (versus in person) or taught by college faculty (versus high school faculty) is associated with lower grades and a lower probability of passing.[11]

- The most common model of DE delivery is certified high school instructors teaching courses at the high school.[12] About 80% of DE students take college courses at their high school.[13]

Dual enrollment funding models vary widely across states, systems, and partnerships. Lowering tuition can lower barriers to access.

- DE is funded through a mix of state, local, K-12, and student/family sources.[14] In many states and localities, community colleges also subsidize DE coursework through discounted or waived tuition and fees.[15]

- States, systems, and partnerships have been aiming to reduce or eliminate students’ out-of-pocket costs to reduce barriers to access.[16]

- The costs to deliver DE can vary substantially based on instructor type, course modality, location, subject, and whether a program provides robust advising and academic supports.[17] DE can be financially sustainable for colleges if they implement DE strategically to expand the pool of future college-going students and increase the number of DE students continuing at their college after high school.[18]

State and local policies determine who gets access to dual enrollment.

- White students participate in DE coursework at almost twice the rate of their Black and Hispanic classmates.[19] English learners and students with disabilities are also severely underrepresented in DE coursework.[20]

- Access to DE is highly variable within states and even among high schools in the same school district.[21]

- One in five districts report nearly equal or higher rates of participation in DE among Black and Hispanic students.[22]

- Colleges and schools tend to rely on standardized placement tests for eligibility, even though researchers question their validity as predictors of college readiness and raise concerns that they perpetuate inequities.[23] An evaluation of a policy change in Ohio found that removing placement testing requirements and providing additional supports results in increased access to DE for Black and Hispanic high school students without changes to course success rates.[24]

High schools and colleges can make dual enrollment a more equitable on-ramp to a college program of study that leads to career-path employment for large numbers of students.

- There is strong evidence that DE—even à la carte DE in relatively small doses[25]—improves academic outcomes for students, including completing high school, enrolling in college, and completing college degrees.[26][27] And DE has been shown to benefit low-income students,[28] Black and Hispanic students,[29][30][31] and students who initially struggled academically in high school.[32]

- Data from Texas suggests that taking DE courses is also associated with moderate earnings gains by age 24, compared to students who take no accelerated coursework. DE students’ earnings were 27% to 40% higher than the earnings of students with no accelerated coursework.[33]

- DE partnerships with stronger results for low-income students and students of color:[34][35]

- engage in active outreach to underserved students and communities, building early awareness in middle school and through community-based organizations, and use alternatives to testing (e.g., high school grades) to determine eligibility;

- align DE course offerings to postsecondary degree programs and embed DE coursework into career-connected high school programs;

- provide college advising to DE students to help them explore career interests and develop a preliminary college educational plan; and

- support student success through high-quality instruction and comprehensive academic supports.

Endnotes

- National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). (2020). Dual or concurrent enrollment in public schools in the United States (Data Point: NCES 2020-125). U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2020/2020125/index.asp

- Shivji, A., & Wilson, S. (2019). Dual enrollment participation and characteristics (Data Point: NCES 2019-176). U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2019/2019176.pdf

- NCES. (2022). Table 225.65: Percentage of public and private high school graduates who took selected dual enrollment courses in high school, by selected student and school characteristics: 2019. In Digest of Education Statistics. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d22/tables/dt22_225.65.asp

- Fink, J. (2025a, September 30). High school dual enrollment grows to 2.8 million. The CCRC Blog. https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/easyblog/high-school-dual-enrollment-grows.html

- Fink, J. (2025b, January 13). How many community colleges fully recovered their enrollments three years after the pandemic? Too few. The CCRC Blog. https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/easyblog/how-many-community-colleges-fully-recovered-their-enrollments-three-years-after-the-pandemic-too-few.html

- Barshay, J. (2023, July 24). Proof points: High schoolers account for nearly 1 out of every 5 community college students. The Hechinger Report. https://hechingerreport.org/proof-points-high-schoolers-account-for-nearly-1-out-of-every-5-community-college-students/

- Fink, J. (2025a).

- Fink, J. (2025a).

- Garcia Tulloch, A. (2023, June 1). Stealth transfer: How former dual enrollment students are disrupting postsecondary education for the better. The CCRC Blog. https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/easyblog/stealth-transfer-disrupting-postsecondary-ed-for-better.html

- Fink, J. (2023). Greater equity in college access through high school/college dual enrollment programs. The Campaign for College Opportunity. https://collegecampaign.org/publication/greater-equity-in-college-access-through-high-school-college-dual-enrollment-programs

- Ryu, W., Schudde, L., & Pack-Cosme, K. (2023). Dually noted: Understanding the link between dual enrollment course characteristics and students’ course and college enrollment outcomes (CCRC Working Paper No. 134). Community College Research Center, Teachers College, Columbia University. https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/publications/dual-enrollment-course-characteristics-course-enrollment-outcomes.html

- Shivji & Wilson (2019).

- Shivji & Wilson (2019).

- College in High School Alliance. (2025). Funding for equity: Designing state dual enrollment funding models to close equity gaps. https://collegeinhighschool.org/resources/dual-enrollment-funding

- Jenkins, D., Steiger, J., & Fink, J. (2025, October 22). How do states fund community college dual enrollment? The CCRC Blog. https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/easyblog/how-do-states-fund-community-college-dual-enrollment.html

- Fink, J., Jenkins, D., Griffin, S., & Garcia Tulloch, A. (2025). College business models for scaling purposeful dual enrollment. Community College Research Center, Teachers College, Columbia University. https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/publications/college-business-models-dual-enrollment.html

- Fink et al. (2025).

- Belfield, C., Jenkins, D., & Fink, J. (2023). How can community colleges afford to offer dual enrollment college courses to high school students at a discount? Community College Research Center, Teachers College, Columbia University. https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/publications/community-colleges-afford-dual-enrollment-discount.html

- Xu, D., Solanki, S., & Fink, J. (2021). College acceleration for all? Mapping racial/ethnic gaps in Advanced Placement and dual enrollment participation. American Educational Research Journal, 58(5), 954–992. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831221991138

- Fink, J. (2025c, April 14). Who has access to dual enrollment and AP coursework at your local schools? The CCRC Blog. https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/easyblog/who-has-access-dual-enrollment-ap.html

- Xu et al. (2021).

- Xu et al. (2021).

- Scott-Clayton, J., Crosta, P. M., & Belfield, C. R. (2014). Improving the targeting of treatment: Evidence from college remediation. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 36(3), 371–393. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373713517935

- Sparks, D., Griffin, S., & Fink, J. (2025). “Waiving” goodbye to placement testing: Broadening the benefits of dual enrollment through statewide policy. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/19345747.2025.2520855

- Liu, V. Y. T., Chelliah, B., Saunders, T., Ju, H., & Viera, C. (2025). The more the merrier? The dosage effect of dual enrollment credits earned in high school on college enrollment and degree completion. Research in Higher Education, 67, 1 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-025-09872-4

- Taylor, J. L., Allen, T. O., An, B. P., Denecker, C., Edmunds, J. A., Fink, J., Giani, M. S., Hodara, M., Hu, X., Tobolowsky, B. F., & Chen, W. (2022). Research priorities for advancing equitable dual enrollment policy and practice. The University of Utah, Collaborative for Higher Education Research and Policy. https://cherp.utah.edu/publications/research_priorities_for_advancing_equitable_dual_enrollment_policy_and_practice.php

- Velasco, T., Fink, J., Bedoya, M., & Jenkins, D. (2024). The postsecondary outcomes of high school dual enrollment students: A national and state-by-state analysis. Community College Research Center, Teachers College, Columbia University. https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/publications/postsecondary-outcomes-dual-enrollment-national-state.html

- For a review, see Appendix A3 in Taylor et al. (2022).

- Liu, V. Y. T., Minaya, V., & Xu, D. (2022). The impact of dual enrollment on college application choice and admission success (CCRC Working Paper No. 129). Community College Research Center, Teachers College, Columbia University. https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/publications/impact-dual-enrollment-application-choice-admission-success.html

- Minaya, V. (2021). Can dual enrollment algebra reduce racial/ethnic gaps in early STEM outcomes? Evidence from Florida. Community College Research Center, Teachers College, Columbia University. https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/publications/dual-enrollment-algebra-stem-outcomes.html

- Liu, V. Y. T., Minaya, V., Zhang, Q., & Xu, D. (2020). High school dual enrollment in Florida: Effects on college outcomes by race/ethnicity and course modality. Community College Research Center, Teachers College, Columbia University. https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/publications/dual-enrollment-florida-race-ethnicity-course-modality.html

- Lee, H. & Villarreal, M. U. (2022). Should students falling behind in school take dual enrollment courses? Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk (JESPAR), 28(4), 439–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/10824669.2022.2100994

- Velasco, T., Ryu, W., Schudde, L., Grano, K., Jenkins, D., & Fink, J. (2025). Promising combinations of dual enrollment, AP/IB, and CTE: The college and earnings trajectories of Texas high school students who take accelerated coursework. Community College Research Center, Teachers College, Columbia University. https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/publications/promising-combinations-dual-enrollment-ap-ib-cte.html

- Fink, J., Griffin, S., Garcia Tulloch, A., Jenkins, D., Fay, M. P., Ramirez, C., Schudde, L., & Steiger, J. (2023). DEEP insights: Redesigning dual enrollment as a purposeful pathway to college and career opportunity. Community College Research Center, Teachers College, Columbia University. https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/publications/deep-insights-redesigning-dual-enrollment.html

- Mehl, G., Wyner, J., Barnett, E. A., Fink, J., & Jenkins, D. (2020). The dual enrollment playbook: A guide to equitable acceleration for students. Community College Research Center, Teachers College, Columbia University. https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/publications/dual-enrollment-playbook-equitable-acceleration.html