The Federal Work-Study (FWS) program is one of the nation’s oldest federal policy tools intended to promote college access and persistence for low-income students. Since 1964, FWS has supported student employees who have applied for financial aid and have unmet need. These students work on campus for about 10 to 15 hours per week in roles ranging from clerical work at the library to research positions in a lab.[1][2] In addition to providing financial assistance, the program may influence students’ academic and labor market outcomes by affecting their schedules, exposing them to new social and job networks, and offering relevant employment experience. But with well-designed, research-based reforms it could have a greater positive impact on students.

What the Research Tells Us

The FWS program is widespread across American higher education and supports a significant proportion of undergraduates each year.

- FWS provides roughly $1 billion annually to about 600,000 students on over 3,000 campuses nationwide.

- The program covers up to 75% of student participants’ on-campus wages.

- One out of every 10 full-time, first-year undergraduates receives FWS support, and more than 33 million students have benefitted from the program since its inception.

Though FWS does not fulfill its original mission to enable students to “work their way through college,” on-campus work experience may improve labor market outcomes in the longer term.

- Today’s typical FWS award is $2,340 per year, which covers only a fraction of average tuition and fees.[3]

- Most college students work part-time even if they do not receive FWS, often in low-skill jobs with no connection to their major and potentially with little consideration for students’ academic schedules.[4][5] By providing flexible, on-campus employment, FWS may increase campus integration and make it easier for students to juggle school and work, though many FWS jobs are also unrelated to students’ majors or career interests.

- In-school work experience may improve labor market outcomes in the longer term,[6][7] in part because FWS students are more likely to have a job relating to their major than similar students who work in non-FWS jobs.[8]

- FWS jobs may help level the playing field for students who cannot afford to take unpaid intern- ships to gain experience.[9]

The impact of FWS on students’ academic outcomes is mixed.

- An offer of FWS is likely to induce some students to work while enrolled, which may interfere with their studies by reducing studying time and causing scheduling challenges.

- CCRC researchers have found that FWS has a small negative effect on students’ first-year GPAs and, in some cases, credit accumulation and graduation.[10] However, they also found that FWS participants have higher rates of persistence, degree completion, and post-college employment.[11]

- FWS may add new links to students’ school-based networks, increase their job’s relevance to their academic work, and give them more reasons to come to campus, thereby increasing their likelihood of attending classes and participating in campus activities. Several studies have found that students with more campus connections are more likely to persist,[12][13][14] and this may be particularly true for minoritized students.[15]

- FWS has never been evaluated using a randomized controlled trial, though one such study is currently underway.[16]

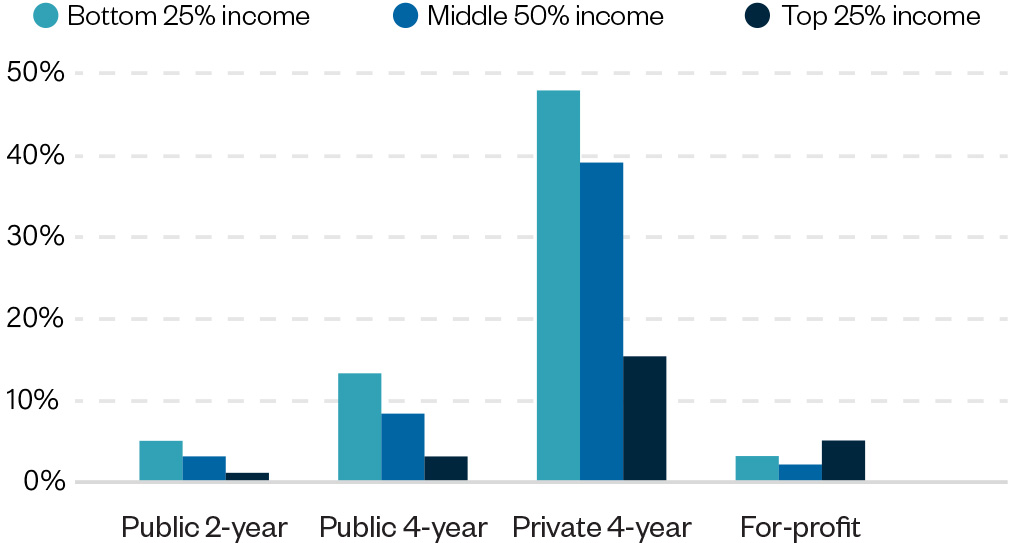

Students at public colleges, especially community colleges, have a much smaller chance of receiving FWS aid than students at private colleges, regardless of family income.

- Unlike other forms of federal student aid, which are awarded directly to students, FWS funds are granted in aggregate to institutions, based largely on historical allocations that tend to favor selective private colleges.[17]

- Colleges have significant flexibility in implementing the FWS program— including determining which students receive awards, the size of awards, and how students are connected to jobs.

- Demand for FWS outstrips supply. Only 16% of institutions award FWS to every eligible student.[18]

- A low-income student at a private four-year institution has nearly a 50% chance of receiving FWS, compared to just a 5% chance for a low-income student at a community college.[19]

- A high-income student at a private four-year college is more likely to receive FWS than a low-income student at a public four-year college,[20] despite evidence suggesting FWS recipients at public institutions derive substantially greater benefits from the program.[21]

Which Students Get FWS Dollars

Source. Tabulations using NCES QuickStats for dependent undergraduates in the Beginning Postsecondary Students 2011–12 survey.

Key Considerations for Federal Policy

- FWS allocation formulas should be updated so community colleges are no longer disadvantaged relative to selective private institutions. FWS allocations could be based on enrollment of Pell-eligible students, or student eligibility could be limited to those below a given income.

- Any reallocation or expansion of FWS funding should build in research studies to track the impacts of the program and inform later policy changes that improve the targeting and effectiveness of funding.

Endnotes

- ^ The College Board. (2012). Trends in student aid 2012.

- ^ U.S. Department of Education. (2009). Federal student aid handbook 2009–2010. Office of Federal Student Aid.

- ^ CCRC tabulations using NCES QuickStats with NPSAS:2016, limited to those receiving FWS.

- ^ Perna, L. W., Cooper, M. A., & Li, C. (2007). Improving educational opportunities for college students who work. In E. P. St. John (Ed.), Readings on equal education: Volume 22 (pp. 109–160). AMS Press.

- ^ Scott-Clayton, J. (2012). What explains trends in labor supply among U.S. undergraduates? National Tax Journal, 65(1), 181–210.

- ^ Light, A. (2001). In-school work experience and the returns to schooling. Journal of Labor Economics, 19(1), 65–93.

- ^ Ruhm, C. J. (1997). Is high school employment consumption or investment? Journal of Labor Economics, 15(4), 735–776.

- ^ Scott-Clayton, J., & Minaya, V. (2016). Should student employment be subsidized? Conditional counterfactuals and the outcomes of work-study participation. Economics of Education Review, 52, 1–18.

- ^ Edwards, K. A., & Hertel-Fernandez, A. (2010). Paving the way through paid internships: A proposal to expand educational and economic opportunities for low-income college students. Demos.

- ^ Scott-Clayton, J., & Zhou, R. Y. (2017). Does the Federal Work-Study program really work—and for whom? Center for Analysis of Postsecondary Education and Employment.

- ^ Scott-Clayton & Minaya (2016).

- ^ Braxton, J. M., Sullivan, A. V., & Johnson, R. M. (1997). Appraising Tinto’s theory of college student departure. In J. C. Smart (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research, Vol. 12 (pp. 107–164). Agathon Press.

- ^ Pascarella, E., & Terenzini, P. (2005). How college affects students: A third decade of research, Vol. 2. Jossey-Bass.

- ^ Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Fischer, M. J. (2007). Settling into campus life: Differences by race/ethnicity in college involvement and outcomes. The Journal of Higher Education, 78(2), 125–161.

- ^ Community College Research Center. (n.d.). Does Federal Work-Study work for students?

- ^ Smole, D. P. (2005). The campus-based financial aid programs: A review and analysis of the allocation of funds to institutions and the distribution of aid to students (CRS Report for Congress). Congressional Research Service.

- ^ U.S. Department of Education. (2000). The national study of the operation of the Federal Work-Study program: Summary findings from the student and institutional surveys. Office of the Under Secretary; Planning and Evaluation Service; Postsecondary, Adult, and Vocational Education Division.

- ^ Scott-Clayton, J. (2017). Federal Work-Study: Past its prime, or ripe for renewal? (Evidence Speaks Reports, Vol. 2, #16). The Brookings Institution.

- ^ Scott-Clayton (2017).

- ^ Scott-Clayton & Minaya (2016).